Author’s Note: In 1989, the Thoed Thai Highland Health Center Project implemented by Tom Dooley Heritage, an American non-governmental organization (NGO), in collaboration with the Royal Thai Government Ministry of Public Health was handed over to Government to assume full responsibility for its continued operations. The five-year Project was a successful international development partnership which provided capacity-building support (funding and training) for its gradual integration into the Thai Rural Health System.

The experience also set the stage for my eventual entry into graduate school in Hawaii, USA — but not before accepting a one-year position with the Catholic Relief Services, another American NGO, which supported refugee relief work on the Khmer border and community health development in poor, rural communities in Thailand.

Chiang Rai Province, Thailand

Though extremely difficult to leave, my time as Project Director at Thoed Thai Highland Health Center in northern Thailand had come to an end. The Thai Government was poised to assume full responsibility for operations of the Project, which had developed an appropriate health service delivery model for preventive and clinical health care by training and facilitating the entrance of local health workers into the Thai National Health System.

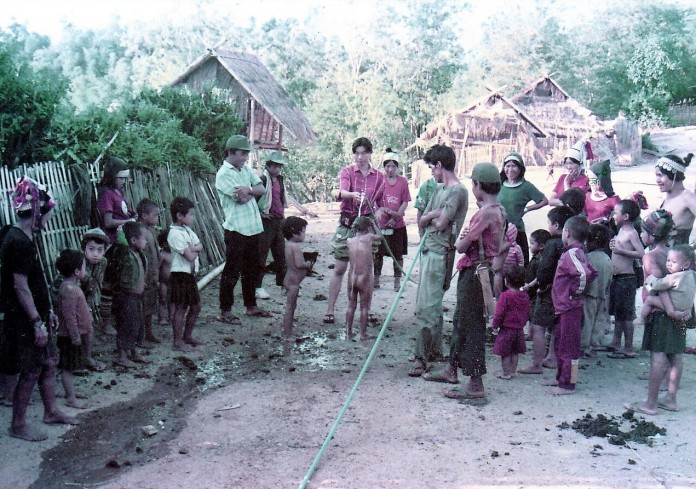

Innovative community-based health and development strategies had been successfully introduced, including gravity-fed village water systems, household gardening, community-based opium detoxification, and vector-borne disease control.

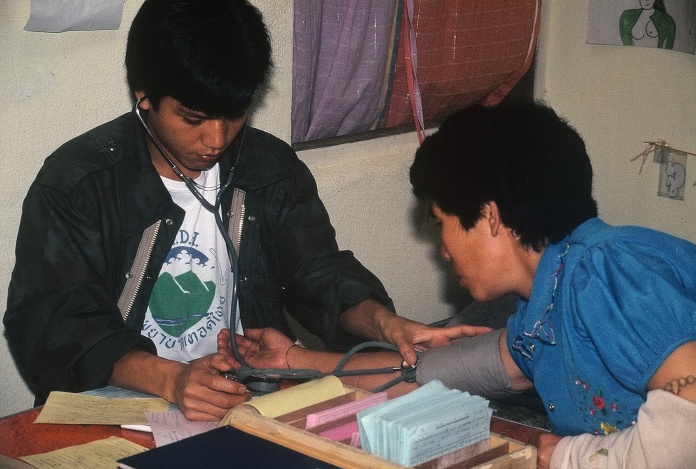

A multi-ethnic cadre of village health workers trained by the Project had been established and were providing basic primary health care services in their local communities as part of the Thai Rural Health System.

Meanwhile, the District Immigration Officer was certain that I was CIA. After all, the area had been saturated with American CIA agents conducting opium eradication. And although I was not a medical doctor, somehow I happened to be the Director of an American health project in the area. Furthermore, I spoke and understood Thai language reasonably well and probably just looked a little too ‘military.’

In many ways, it was like running a summer camp. Nights lit by serene lamplight, a fun, youthful staff, lively parties, variety shows. Nine languages were spoken at our health center, representing the various local ethic groups (and three Americans) that comprised our staff. But we used Thai language for general communication and staff meetings.

Exhilarated and somewhat traumatized by the toughest and most intense work experience yet, I reflected on the many harrowing experiences, such as being pulled across a raging torrent on a swing-like board and cable where a bridge had once stood, before being washed away in the annual flooding due to widespread deforestation in the surrounding hills. Or the night a huge storm ripped through our area tearing the roofs off a dozen houses and knocking down ten others.

All was quiet following the violent storm. But there had been heavy shelling along the border all week long and insurgent fighters belonging to a rival drug warlord had reached the perimeter of our village. Wounded soldiers were arriving at a makeshift clinic across the road run by some of our health staff who were loyal to the local drug war lord, Khun Sa.

Eighteen of us living at the health center boarded the hospital truck to evacuate down the mountain, but we decided the washed out road — at night and with numerous trees down — would be more dangerous than to chance lying low at the hospital.

And of course, each 13 kilometer journey up our treacherously steep and slippery mountain track was an adventure in itself, hanging on for dear life with the rest of the passengers – some of them vomiting – in the back of the violently pitching pickup truck.

Riding with my favorite Chinese drug-running driver – we barreled wildly along the heavily rutted road past flooded rice paddies, climbing higher into the mountains that filled the horizon. Meeting other trucks head-on and lifting them out of the ruts to get past, then flying through villages as dusk settled over the hills — with a full moon on the rise — and arriving home in time for a warm beer and a plate of fried peanuts at our only restaurant.

Bangkok

In stark contrast to my 18 months in the mountains (with no electricity or running water), it didn’t take long to settle into the comfortable ‘expat lifestyle’ based in Bangkok with the Catholic Relief Services, an American NGO which supported health and development projects in Thailand and provided comprehensive primary health care services for over 30,000 Khmer refugees living in camps along the Thai-Cambodia border.

As Office Manager, and later as the Acting Country Representative, I controlled an annual budget of US$ five million, managed 120 employees in five offices nationwide, partnered with Government, NGOs and other international agencies, and ultimately negotiated major revisions to the CRS Country Program strategy to move from a welfare and emergency relief profile towards longer-term, sustainable social and economic development.

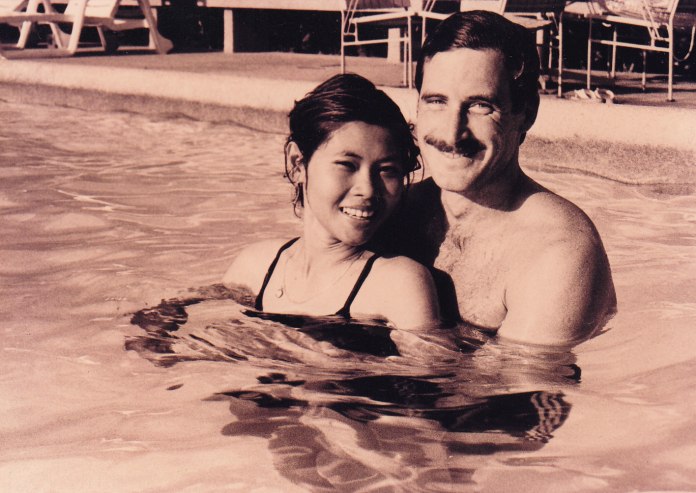

Joining friends from work, weekends in the nearby province Kanchanaburi provided a refreshing break from Bangkok’s notorious traffic snarls and choking air pollution. We stayed in floating bungalows on the River Kwai, and would cool off in the river before heading into town each night for some good food and drink.

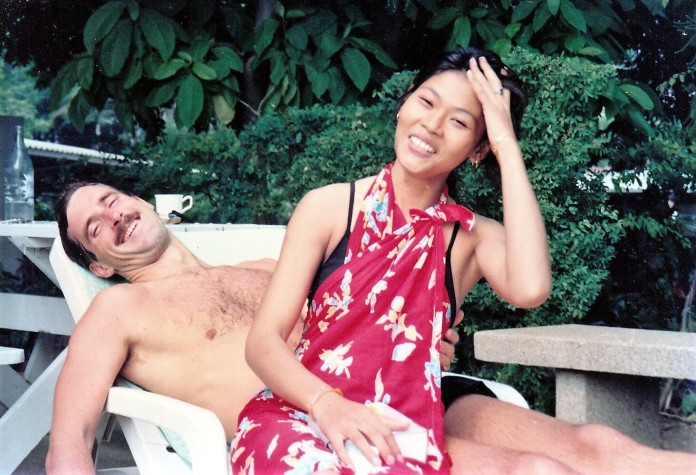

At home in Bangkok, lazy weekends were spent lounging by the pool feasting on ripe, sweet mangoes with sticky rice and coconut cream.

Life was pretty easy living the high life in Thailand’s cosmopolitan capital city, with a luxury apartment and pool, an air-con office, a lovely girlfriend and a growing circle of friends all sharing the fat and happy expat lifestyle in our version of ‘The Modern Raj.’

A Chiang Rai Reunion

When I returned to northern Thailand the following year for a visit, the rains had begun. So I kicked off my shoes, donned my swim trunks and made my way barefoot, slipping, sliding and sweating the thirteen kilometers to Thoed Thai Highland Health Center.

The mountain air was fresh and still. I felt absolutely high upon returning to Thailand’s northern frontier — unique and still mostly untouched, with the distant sound of cowbells, a few birds singing, and the full chorus of frogs and insects at night — and a cascade of emotions and memories from those exhilarating times living in the hills.

Breathing in the cool, fresh country air, I enjoyed a swim in our local spring-fed reservoir, hiked to a few nearby hill tribe villages and received a warm welcome from all.

But the wind was shifting and the time had come to set a new course. I would have to leave my friends and give up this extraordinary ‘expat lifestyle’ — after nearly a decade overseas — and return to America to begin my graduate studies in Hawaii, USA.

Stay tuned for more stories, coming soon!

You can read more about Jim’s backstory, here and here.

Note: An expatriate (or ‘expat’) is a person temporarily or permanently residing in a country other than that of the person’s upbringing. The term is often used in the context of professionals or skilled workers sent abroad by their companies, rather than for most ‘immigrants’ or ‘migrant workers.’

[…] Source link Lifestyle […]